A Review of Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Jasper Johns, the American painter, sculptor, and printmaker, celebrated his ninetieth birthday on May 15, 2020. To commemorate it, the most comprehensive retrospective of his work, Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, was planned to open in that same year. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the show’s opening was postponed until September 29, 2021. On this date, the exhibit simultaneously opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The almost 500 works of art in the show were divided across these two different venues. The Whitney portion was curated by Scott Rothkopf; the Philadelphia Museum of Art portion, by Carlos Basualdo. Two halves of a whole.

This unique mise en scène for Mind/Mirror seemed, to me, to invite two impressions: one from the vantage of artistic knowledge with an appreciation for the psychoanalytic method and another from the perspective of the psychoanalyst that appreciates art. Beyond the actual setup of Mind/Mirror, Johns’s oeuvre offers the ideal space for binate views, for contrasts and reflections, since much of his work is devoted to the twin concepts of the mirror and the double.

On a beautiful, sunny fall day, I found myself in New York City’s meatpacking district, which since 2015 has been home to the Whitney’s latest space, designed by Renzo Piano. Here, amid large, open galleries—some of them with views of the Hudson—Johns’s work appeared to be grouped primarily by themes, despite the exhibit’s chronological order. A couple of months later, on a cold January day, I made the trip to Philadelphia to see the exhibit’s second half. In this city, the Museum of Art is in the Fairmount neighborhood, its home since 1929. The famous steps that Rocky Balboa climbs in the film Rocky (1976) lead to the Museum’s main entrance. At the bottom of the steps, a sign reminds the visitor that the museum was once a reservoir. Here, the museum galleries—reminiscent of those found in European museums—take the viewer through Johns’s work in a symmetrical, orderly manner. The viewer is invited to enter and follow Johns’s work chronologically in a mostly linear tour through the windowless galleries.

Freud and Lacan wrote extensively about their approach to creative works: art, literature, music, and film. One of the ways Freud viewed artistic expression was as a sublimation, a process in which libido is deflected from its original aim to non-sexual and non-conflicted activities. This desexualization of libido opens the path to creative endeavors. For Freud, literature, painting, and sculpture offered, like dreams, a road to the unconscious, an entrance to the creator’s psyche. Like Freud, Lacan had significant interest in art, literary and visual. And even though he referenced sublimation in his seminars, Lacan felt that it was undesirable for psychoanalysis to say anything about the psychology of the artist. He suspended the inquiry into the creator’s motive or intent. As, for Lacan, the unconscious is structured like a language, the analysand’s discourse—or, as relevant here, the discourse of the creative work—needs to be treated like a text.

Jasper Johns’s work is extensive and influential, and, naturally, its potential connections to his biography have been discussed profusely. His growing up, his parents’ divorce, his military experience, his romantic relationship with Robert Rauschenberg, his reclusiveness—all have been subjects of significant inquiry. Johns is well-known for not explaining his work or process. In interviews, he is reticent, perhaps not wanting to be the subject of exploration.

Johns’s work has been associated with abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada, and pop art. The Neo-Dada movement, in particular, sought to highlight the idea that the meaning in art was something personal that could only be defined within an individual. Neo-Dadaists thus believed that the intent of the artist was irrelevant and that meaning was created through the viewer’s interpretation—one can hear here the echoes of Lacan.

Although walking through an art exhibit does not involve sitting in the room with an analysand as the clinical process unfolds, I believe the former asks me to do something similar to what I would do in the latter case: enter the space without preconceptions and see how the experience of the material unfolds.

As Freud says, “the attitude which the analytic physician could most advantageously adopt was to surrender himself to his own unconscious mental activity, in a state of evenly suspended attention, to avoid so far as possible reflection and the construction of conscious expectations, not to try to fix anything that he heard particularly in his memory, and by these means to catch the drift of the patient’s unconscious with his own unconscious.”[1]

At the entrance to the Philadelphia portion of the show, one is greeted by one of Johns’s iconic flags, and one learns that circa 1954, when Johns was 24 years old, he destroyed all of his work with the goal of not trying to be an artist but simply being one. Soon after this, he painted his first flag. From there, one moves to early works that incorporate ordinary objects (e.g., fountain pens, spoons) and to his well-known Fool’s House, which contains a large broom. Incorporating these quotidian objects amid abstraction blends reality into art or, as the wall text suggests, tests “the relationship between image, language and object.”[2]

Moving along the space, numbers and colors come into view. We learn that, since the 1950s, Johns has created more than 170 paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures that feature numbers, usually as individual figures, as sequences, or as various images superimposed on one another. One can appreciate the tracing and retracing of elements with which the mind is well-acquainted: repetition, precision, compulsion, appearing and disappearing, figure and ground in an intrinsic dance.

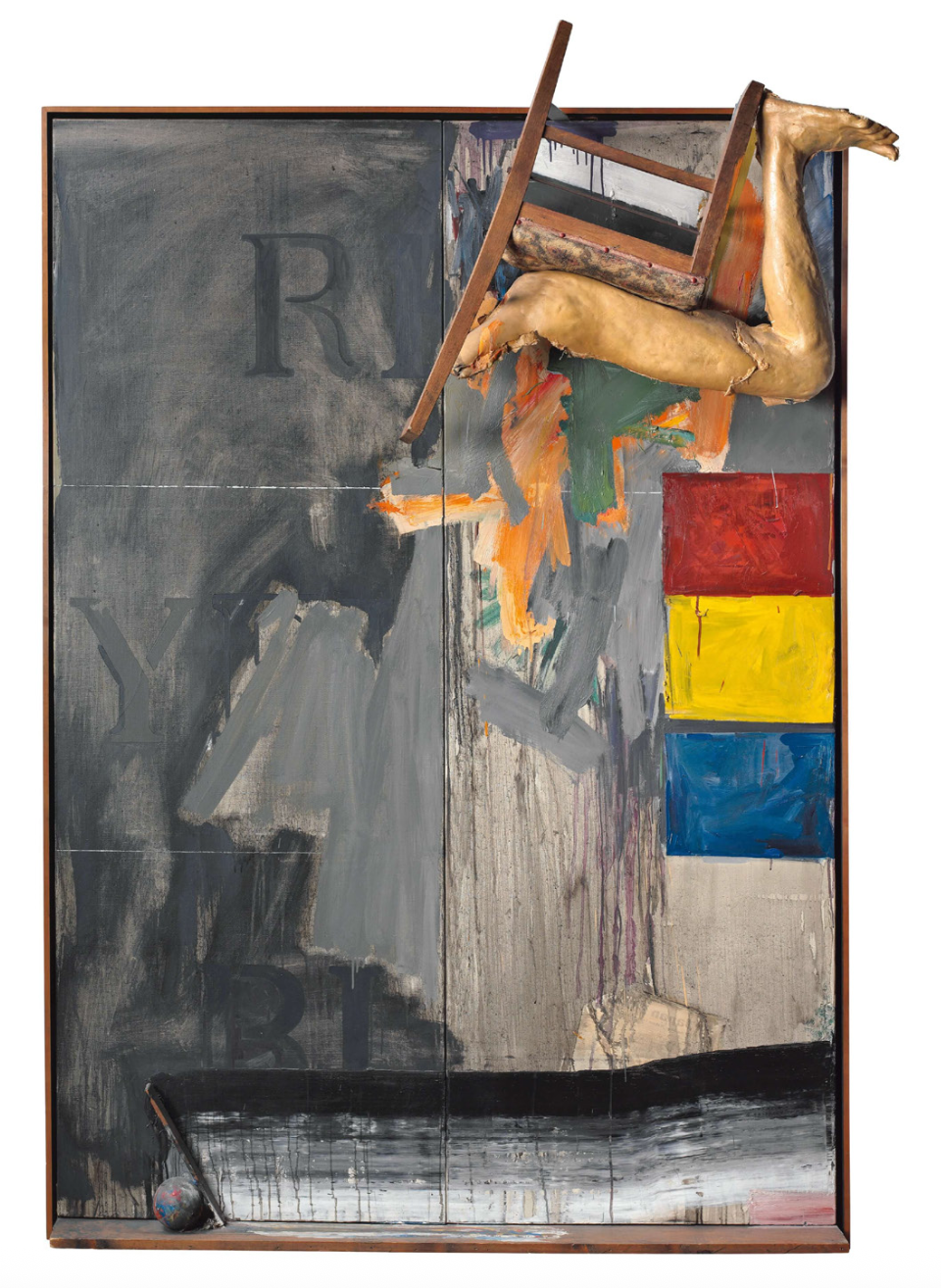

The Leo Castelli period (1960) follows. Castelli, a prominent art dealer, represented Johns in his first solo exhibition and continued to do so until Castelli’s death in 1999. In the space dedicated to Japan, Johns’s well-known piece Watchman comes into view, along with other works influenced by his time in this country. One reads that while Johns was traveling in Japan, he wrote about the differences between the figures of the “watchman” and the “spy.” The wall text quotes Johns: “The Watchman falls ‘into’ the ‘trap’ of looking,” and “tak[ing] away no information,” while “[t]he spy must remember”—remembering both “himself and his remembering. The spy designs himself to be overlooked. The watchman ‘serves’ as a warning.”[3]

After this, the room titled Doubles and Reflections comes into view. In this space, symmetrical structures, mirrors, doubles, and reflections are the primary focus, bringing to mind image and process and allowing for the emergence of something quite ephemeral. As if in the process of capturing an image, something is forever lost. Lacan’s méconnaissance (misrecognition) comes to mind.

In the gallery titled Nightmares, one learns that, in the 1980s, Johns’s work was marked by a somber mood and perplexing images. The work from this period that the Whitney’s exhibit contains comes also to mind, the two halves becoming a whole. The work is engaging, simultaneously beautiful and frightening. The home(l)y (heimelig/heim-lich) among the unhomely (unheimlich).

The last stop contains Elegies in Light. Johns’s more recent work is here. Motifs that one recognizes from his early work, transformed, reawaken with perhaps—if possible—more directness and maturity. Skulls, the vacillation of figure and ground, abundant white space, and delicate, tenuous cloths hanging create an intimate yet ineffable emotion.

Moving from moment to moment in the exhibit, I found myself being pulled in different directions. Johns’s insertion of the familiar amid the unfamiliar, coupled with his doubles, evokes Freud’s uncanny. Objects and part objects, the play of construction and deconstruction, and the iteration of mirrors and reflections give rise to feelings of loss and alienation. The repetition of themes, Johns’s tracing and retracing, brings to mind the repetition compulsion or—perhaps much more—the feeling that, in the act of repeating, the desired object consistently evades us, and that which we want but can’t define is consistently lost. The chromatic and the achromatic may suggest the dance of life and death, the interdependence of Eros and Thanatos.

The purity of Johns’s aesthetic—its blending of permanence and impermanence—filtered through me as I drove back home from Philadelphia. This brought to mind the walk that Freud takes with a young poet (presumed to be Rilke) on a summer day, recounted in On Transience (1915), one of my favorite essays by Freud. Freud writes:

A flower that blossoms only for a single night does not seem to us on that account less lovely. Nor can I understand any better why the beauty and perfection of a work of art or of an intellectual achievement should lose its worth because of its temporal limitation. A time may indeed come when the pictures and statues which we admire to-day will crumble to dust, or a race of men may follow us who no longer understands the works of our poets and thinkers, or a geological epoch may even arrive when all animate life upon the earth ceases; but since the value of all this beauty and perfection is determined only by its significance for our own emotional lives, it has no need to survive us and is therefore independent of absolute duration.[4]As a 24-year-old, Johns destroyed all his work to begin again, driven by his desire not to try to be an artist, but in fact to be one. In his fifties he created a series of prints titled Usuyuki, Japanese for light snow (something that passes quickly). The name of this series of works, largely composed of densely crosshatched lines, comes from a Kabuki play that has been described by Johns as being about “the fleeting quality of beauty in the world.”[5]

In his most recent work done as an octogenerian, there is something quite sublime: figure, ground, and white space giving a sensation of presence and absence, vanitases of skeletons in different poses and attires, almost as if narrating the many poses we take in life. On Mind/Mirror's opening day, Time published a very short interview with Jasper Johns (he replied via email). The three questions I am selecting to include here appear to say it all.

For what in your life do you feel most grateful?

I am lucky for being able to devote myself to work that remains interesting to me. . . .

Your work is sometimes regarded as chilly or detached. Do you understand that perception?

No.

Robert Rauschenberg said that “Good art can never be understood.” Do you agree?

Not with the language. I don’t know that art can be understood in any final way, but a search for understanding tends to open one’s eyes rather than close them.[6]

If Johns’s goal was to be an artist, perhaps he achieved it the moment he let go of his work to begin again—as if, as a young man, he already understood the fleeting nature of life. His work transcends the conscious, and, like the psychoanalytical process, opens the eyes instead of closing them.

[1] The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 18 at 239 (James Strachey trans. 1955) [hereinafter SE, followed by volume number].

[2] Wall text, Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, Pa. Museum of Art, Sept. 29, 2021–Feb. 13, 2022.

[3] Id. (quoting Jasper Johns, Sketchbook page, Book A, 1964, in Carlos Basualdo & Scott Rothkopf, Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror 139 (2021)).

[4] SE vol. 14 at 306.

[5] Basualdo & Rothkopf, supra note 3, at 113.