Art on Art:A Review of Tár

Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.

Pablo Picasso (1939, p. 10)

The 2022 art film Tár is suffused with anagrams. In one scene, the film’s title character, Lydia Tár, creates the anagram “at risk” from the name of a former student of hers, Krista. In another, Lydia’s assistant Francesca creates the anagram “rat on rat” from the title of Lydia’s upcoming book Tár on Tár. Besides “rat,” though, the other possible anagram of Tár (in English) is “art,” an anagram the film hints at, even if it never explicitly sets it forth.

Tár is a spectacular film that leaves ample room for speculation and touches on controversial themes, some au courant, some longstanding: the #MeToo movement, cancel culture, divergences between millennial/Gen Z culture and boomer culture, the role of social media in shaping opinions, and, perhaps most significant, whether there should exist a separation between creator and creation.

Apropos of this last theme, a few weeks ago, Dr. Candace Orcutt shared with me her article “Masud Khan: The Outrageous Chapter 4” (2019). In this article, Orcutt writes:

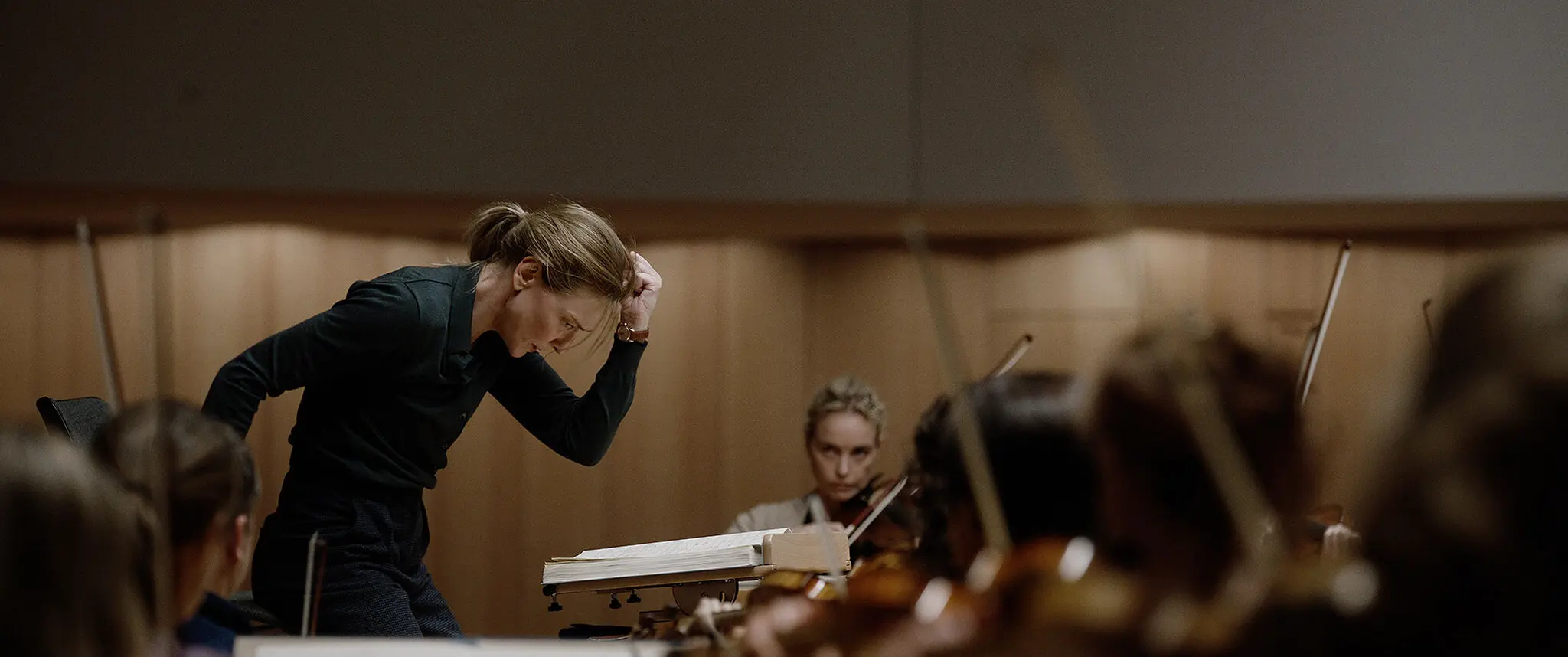

Khan’s own work now tends to be dismissed, although it consistently demonstrates Khan’s genius for explicating the genius of his time. In particular, his work on the schizoid personality, the “hidden self”—extending the thinking of Fairbairn, Guntrip, and Winnicott—further details the theory of the Self as the primary psychic component. His concept of “cumulative trauma” predates by years contemporary theory on the influence of dysfunctional relationship on the early development of personality. His book on perversion is innovative, notably in depicting the distortion of transitional phenomena in the unintegrated collage of early development, with the fetish as a miscarriage of the transitional object. How can such significant achievement lack due recognition?The figure at the center of Tár’s exploration of these questions, Lydia Tár, is a brilliant, world-renowned maestro, EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony winner), professor, mentor, and benefactor. The movie opens with Adam Gopnik from The New Yorker interviewing Lydia on account of the upcoming performance of Mahler’s fifth symphony that she will conduct and the release of Tár on Tár on the date of her fiftieth birthday. The long-awaited performance (postponed because of COVID-19) is only a month away, and rehearsals are about to start. Before Lydia walks onstage to be interviewed, we see some of the compulsions she exhibits throughout the movie: she mutters unintelligible sounds, grimaces, brushes her face and sides, deeply concentrates, sanitizes her hands. She then swallows some pills, attempts to control her anxiety, and enters into character.

Those familiar with Khan’s story will probably respond as follows: “He was anti-Semitic, he slept with his patients, and his obnoxious social behavior was untreatable through psychoanalysis.” There is a basis for all these arguments, but are they enough in themselves to justify disregarding valuable writing? And how valid are the arguments in themselves? (pp. 489-490)

Through the interview with Gopnik, we learn that Lydia is one the most important musical figures of our time. She is a piano performance graduate from the Curtis Institute, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard, holds a PhD in musicology from the University of Vienna, and spent five years performing ethnographic fieldwork among the Shipibo-Conibo people in Peru. She began her career as a conductor with the Cleveland Orchestra (one of the so called “big five”) and was a protégé of Leonard Bernstein (a Mahler expert). She created the “Accordion Conducting Fellowship” for female conductors, and, since 2013, she has been the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. Although Lydia has conducted all of Mahler’s symphonies with different orchestras, the fifth is the only one that she has not conducted as the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. This final Mahler performance will allow Deutsche Grammophon to offer in one box set all of the Berlin Philharmonic’s performances of Mahler’s symphonies conducted by Lydia.

This interview foreshadows many of the key questions the film explores. Gopnik mentions issues of gender bias, diversity, equality, interpreting Mahler, and time and the role of a conductor. On the last point, he suggests that people might see a conductor only as a “human metronome.” Although Lydia somewhat agrees, she elaborates on the role of time in a piece of music: “Time is the thing. Time is the essential piece of interpretation. You cannot start without me. See, I start the clock. Now, my left hand shapes, but my right hand, the second hand, marks time and moves it forward. . . . Now, the Illusion is that, like you, I’m responding to the orchestra in real time . . . The reality is that, right from the very beginning, I know precisely what time it is and the exact moment that you and I will arrive at our destination together.”

Perhaps this is exactly what happens in the film. As we move though the narrative—doubting at times what is real and what is more a product of Lydia’s subjective experience—Lydia is conducting, shaping, moving. We, as the audience, arrive at the destination together with her. In a description of the Shipibo-Conibo people’s understanding of time’s relationship to music, Lydia explains that “the Shipibo-Conibo only receive an icaro, or song, if the singer is there, right? On the same side of the spirit that created it. And, in that way, the past and the present converge. It’s the flip sides of the same cosmic coin.” In this, she believes she differs from Bernstein, who, according to her, believed in teshuva (a Hebrew word at times translated as “returning” or “repentance”; the ten days of teshuva from Rosh Hashana to Yom Kippur mark a significant time for repentance and returning to the path of righteousness).

However, Lydia does not seem to believe that one can go back in time and transform one’s past deeds. In many ways, there’s an inevitability in what appears to happen to Lydia in the film—what the audience might view as her self-destruction or destruction by others, precipitated by her alleged romantic relationships with her students or mentees. There is no repentance or regret on Lydia’s part; just that moment in time when past and present converge. Somewhat reminiscent of the “block universe” theory of time, the film acts as a four-dimensional block of time that already contains all that has happened, is happening, or will happen. Time itself does not correspond to our physical reality, and our conventional perception of time as linear is an illusion (just like how, per Lydia, the audience perceives the conductor as responding to the orchestra, rather than perceiving the conductor as always knowing and anticipating, with the orchestra responding to that anticipation). Put otherwise, the film contains all the letters needed to compose a word, a single unit of meaning; the sequence in which we read those letters, the particular anagram we choose, corresponds to the meaning we perceive.

In speaking about the Italian-French conductor Jean-Baptiste Lully, Lydia notes that, to mark time when conducting, he would pound a long, pointy staff on the floor, and that, on one occasion, he stabbed his foot while conducting. Lully then died of gangrene from the incident. In a similar vein, as the film unfolds, we begin to see how Lydia has figuratively stabbed herself in the foot, as many of the transgressions she is alleged to have perpetrated begin to come to light. But Lydia has no intention of changing course, even after Krista kills herself. Lydia approaches a young cellist with whom Lydia has become infatuated and begins the process again. Lydia’s partner, Sharon, is a witness to—and is effectively complicit in—this process. Sharon is totally aware of Lydia’s infidelities and seems to have a dependent, ambivalent relationship with Lydia. In the end, Sharon leaves Lydia. An open question is whether Sharon perhaps had been (along with Krista and Lydia’s assistant Francesca) orchestrating the destruction of Lydia all along.

As Lydia and Gopnik discuss, it’s believed that Mahler wrote the fourth movement of his fifth symphony, the adagietto, for his wife Alma when he was very much in love with her (later on, she had an affair with Walter Gropius—Mahler sought Freud when his marriage was having difficulties). When Leonard Bernstein conducted this movement at Robert Kennedy’s funeral in 1968, he played it “as a mass” lasting 12 minutes. When Lydia is asked how she would play it, she responds that she would play it not as a mass, as her mentor did, but as a song of young love. When she is asked how long the movement will last, she states 7 minutes. Evidently, love and fidelity do not have a long-lasting hold on Lydia. Love is transient. However, what Lydia does believe in is the power of music.

In yet another magnificent but controversial scene, Lydia and a young Julliard student, Max, engage in the following conversation after Lydia opines that “[g]ood music can be as ornate as a cathedral or bare as a potting shed“ and that conducting music should “actually require[] something of you.“ She asks Max about Bach's Mass in B minor; he responds that he is “not really into Bach.“

Lydia: Have you ever played or conducted Bach?Lydia then asks Max to indulge her and join her at the piano, where she proceeds to play Bach. She says that there is a humility in Bach and that music is not an answer but a question that involves the listener. Max compliments Lydia on her piano-playing but states “white, male, cis composers . . . just not my thing.”

Max: Honestly, as a BIPOC, pangender person, I would say Bach’s misogynistic life makes it kind of impossible for me to take his music seriously.

Lydia: Come on. What do . . . what do you mean by that?

Max: Didn’t he sire like 20 kids?

Lydia: Yes, that’s documented. Along with a considerable amount of music. But I’m sorry, I’m . . . I’m unclear as to what his prodigious skills in the marital bed have to do with B minor. Sure. All right, whatever. That’s your choice. After all, “a soul selects her own society.” But, remember, the flip side of that selection closes the valves of one’s attention. Now, of course, siloing what is acceptable or not acceptable is a basic construct of many, if not most, symphony orchestras today, who see it as their imperial right to curate for the cretins. So, slippery as it is, there is some merit in examining Max’s allergy. Can classical music written by a bunch of straight Austro-German churchgoing white guys exalt us, individually as well as collectively? And who, may I ask, gets to decide that?

“Don’t be so eager to be offended,” Lydia responds. “The narcissism of small differences leads to the most boring conformity.”

A video clip of this exchange is ultimately marshalled on social media as evidence against Lydia’s character. Despite the intensity of the dialogue, the recording on social media takes that dialogue out of context and distorts and rearranges it to create a message that fits. (It does not matter that recording this exchange violated the rule of a technology-free zone inside the school.)

Much of Lydia’s background is not provided to us. We do understand that she does not visit her mother when she is in New York, postponing her visit to “next time.” However, almost at the end of the film, she returns to hide out at her family’s modest home, where we see that her name isn’t even Lydia. I have read that one piece of information that was left out of the movie is that Lydia’s mother was deaf and that Lydia has misophonia (Arthur, 2022). Lydia’s acute sensitivity to sound takes on new meaning in a world where her mother was deaf. Perhaps the director, Todd Field, did not want the audience to have too much insight into Lydia’s character. This is one of the great things about this film. Lydia says that playing Mahler’s fifth is like reading tea leaves and that we don’t know his intention. The intention of Tár is likewise open to multiple interpretations, multiple avenues. For me as a psychoanalyst, the omission of Lydia’s mother’s deafness points in various directions. Perhaps one of them is Freud’s character types. However, the idea that attracts me the most is that of art and artist, creator and creation.

There is no doubt that Lydia created herself; just like she composes music, she is the author of herself. But as her alleged transgressions catch up with her, the surrounding society, and, in particular, social media, also shape her—social media as “the architect of [the] soul,” as Lydia puts it. Her Wikipedia page is edited; video clips of her interactions are edited to create a narrative. Amid public backlash against Lydia, there is even a suggestion from the Accordion fellowship’s board that Lydia should compose her own version of the story. Even at the end of the movie, when we see Lydia in a role so far removed from that of the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic—now (spoiler alert) as a conductor of videogame scores—we see how she takes her role seriously. She studies the score, she lectures the orchestra, and she owns the podium; the podium is her home.

Creator and creation. Do the human misdeeds that are rooted in human development, in a relational past, in trauma, in a social milieu, in the vicissitudes of our instincts, in death and life cancel (as cancel culture does) a gift, a talent, a possible sublimation? And, as Lydia says, who gets to decide that? One might say “who gets to cast the first stone?” In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930/1961), Freud contends that “love thy neighbor as thyself” is a strong defense against human aggression and an impossible expectation of the cultural superego; denial of aggression is displaced in the judgement of others, in casting many stones (pp. 109-112). Freud saw hostility among groups of people, polarization among people that are more similar than different, as a manifestation of this innate disposition for aggression and a desire to claim a distinction of identity. Freud referred to this as the narcissism of small differences (1930/1961, p. 114) (“Narzißmus der kleinen Differenzen” (1930/1991, p. 474)).

Lydia is a fictional character that, hopefully, makes us question not only this narcissim of small differences but also weather human fallibility may obscure a sublime creation, whether it is music, art, or psychoanalytical writings.

references

Arthur, K. (2022). Women do it better: Cate Blanchett and Michelle Yeoh on creating iconic characters from roles written for men. Variety.Field, T. (Director). (2022). Tár. Focus Features.

Freud, S. (1961). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 21, pp. 64-145). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1930)

Freud, S. (1991). Gesammelte Werke: chronologisch geordnet (Vol. 14, pp. 421-506). Imago Publishing. (Original work published 1930)

Orcutt, C. (2019). Masud Khan: The outrageous chapter 4. Psychoanalytic Review, 106(6), 489-508.

Picasso, P. (1939). Statement by Picasso: 1923. In A. H. Barr, Jr. (Ed.), Picasso: Forty years of his art (pp. 9-12). The Museum of Modern Art.